Around Christmas of last year I stopped listening to podcasts. That was a big change. Prior to Christmas, I listened to podcasts during all of my breaks, walks, exercise, chores, errands, and commutes. Whenever I wasn’t interacting with someone or studying for my marriage and family therapy licensure exam, I was listening to podcasts.

I love listening to podcasts. I heard someone say that this is the second great age of radio, and I agree. I wasn’t there for the first, so I don’t get a vote, but I suspect that this one is better. Listening to podcasts, my days were full of super high quality radio shows: stories, lectures, news, analysis, entertaining, educational, emotionally moving, on demand, whenever, wherever. It was wonderful.

Once I set the date for taking my LMFT exam, though, I also started thinking about starting my private practice. Despite a private therapy practice being my fond desire for over a decade, despite having worked hard all that time to prepare for this moment, I started to feel anxious. That anxious feeling helped me realize that I needed to ditch the podcasts and focus on my own thoughts and plans. I’ve studied for exams my whole life, and I can do it with podcasts in my life. Starting a business is new and a big deal for me. I needed to hear everything my brain had to say on the topic, wrap my head around all the options, give myself mental space for it. Podcasts were taking up almost all of that space. A lot of mental problem solving does happen behind the scenes, so to speak, in parts of our brains that do not report directly to our conscious awareness, so a lot of problems are best solved by concentrating hard for a while and then completely taking your mind off of them for a while, maybe by listening to a podcast. The set of problems I’ve been working on are not like that. They require no burst of inspiration, just continued concentration. For example, what should my informed consent form have in it? I need to read and understand the relevant laws and ethical codes, read through my notes, look at the various examples I’ve collected and are available online, and write one. My task is thoroughly and effectively integrating and using existing information, not solving or creating new problems or solutions.

I started listening to podcasts in 2006. I had a broken heart and needed help derailing some persistent, not-useful thoughts. It worked wonderfully. My mind could trace the grooves of great thinkers and storytellers instead of loop unhappy thoughts. The only side effect was learning a ton. I listened to easily thousands of hours since then. My Planet Money listening alone totaled more than 150 hours of learning about economics. By the time I quit, I was listening to almost every episode of over 20 podcasts. (See the full list below.) Podcasts on so many different topics made for lots of great cross-referencing of information in my mind and generated lots of good questions. Quite a bit of what I’ve written about in this blog started off with my attempts to bring two or three podcast narratives to terms with each other.

Quitting means learning less overall, but more deeply in one area: casting a learning net that goes deep but much less broad. I’ve been reading business articles, buying malpractice insurance, looking into potential office spaces, figuring out insurance panels, working on a marketing plan, making a budget, learning about bookkeeping and taxes, and on and on. When I take my now silent walks or drives I can watch my thoughts working through these topics and take note of any new clarity, priority, or question. The only problem is that it’s boring. With podcasts I was almost never bored. Without them, it’s very common. I’ve experienced way more boredom in the last few months than in all of my last ten years combined.

My first whiff of this change came while listening to Joshua Waitzkin on the Tim Ferriss podcast. Waitzkin is a former world champion in both chess and tai chi push hands, and a compelling speaker. At one point he says, “I like to cultivate moments of silence in my life,” and I had to stop the tape. I thought, “That sounds wonderful! That sounds useful! That sounds like something I’d like to do. But I never do that.” More recently I read Cal Newport’s Deep Work (thanks to Blake Boles), in which he sings the praises of boredom. He says that resisting distraction, remaining bored, is like calisthenics for the mental muscle you use to do the difficult, focused, high value work that he calls “deep work.”

I’m sold, at least for now. I’m cultivating plenty of moments of silence and I’m doing a fair amount of deep work and benefiting from it enormously. It’s great to feel and be productive. But I can feel the tension. Integrating what I catch in my broad net is a big part of who I am and what I have to offer my clients and community. My choice is clear when it’s between listening to podcasts or launching my private practice effectively and efficiently. But once it’s up and running (and paying the bills) I’ll be listening again, though I hope with a better sense of when I’ll benefit by turning them off to take a silent walk around the block.

—————-

Complete list of podcasts as of 12/25/2016:

99% Invisible – Great stories about how human design effects our lives and culture. Interesting but also often inspiring or moving.

Bulletproof Radio – Dave Asprey interviews interesting people about biohacking. He does a fair amount of self-promotion, but his guests tend to be good and he presents some really interesting ideas. I was listening to about half of his episodes. If you want to check one out, go through his archives and choose a topic you’re interested in.

The Daily Evolver – I really miss this one. Jeff Salzman analyzes current events from the perspective of Ken Wilber’s integral metatheory. It’s often political, and he’s a rare optimistic voice on the progressive side. My favorite episodes, though, are when he interviews Keith Witt, an integral psychotherapist. Check out whatever he’s posted most recently with Witt. Those episodes are called “The Shrink & The Pundit.”

The Ezra Klein Show – A wonderfully nerdy political show with great interviews that go deep.

Fareed Zakaria GPS – Intelligent current events analysis each week, from a world-centric perspective. I miss this one too.

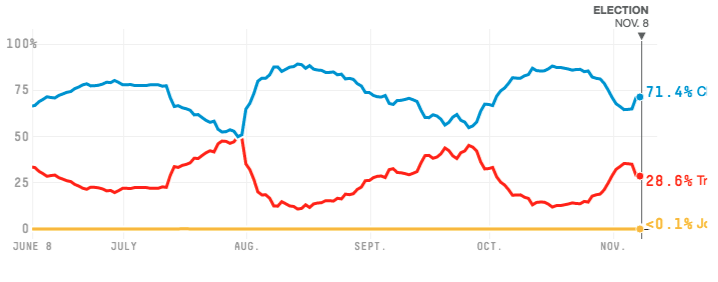

FiveThirtyEight Politics – Nate Silver and his team bring much needed data and data analysis to current events and news.

Freakonomics Radio – Relentlessly counterintuitive findings from economics.

Hidden Brain – A good psychology podcast from NPR.

Imaginary Worlds – Eric Molinsky talks about sci-fi and fantasy world building in popular culture. If you’re a fan, check out his series on Star Wars.

Invisibilia – Another psychology podcast, very engaging.

Judge John Hodgman – My comic relief podcast. John Hodgman hears and rules with wisdom and hilarity on real disputes.

Left, Right & Center – Weekly political analysis from a liberal, conservative, and centrist. This show taught me that political analysis is all about outcome-irrelevant learning.

Longform – Good interviews with authors about writing.

The Memory Palace – Fantastic, very short, poetic, moving episodes about historical events, usually on a personal scale. So good.

More Perfect – Fascinating stories about US Supreme Court decisions.

The New Yorker Radio Hour – This started off as interviews with New Yorker writers about current articles, and has morphed into more of an art/culture/politics variety show. I preferred the former version, but it’s still really good, as one would expect from The New Yorker.

The New Yorker: Poetry – Short episodes in which Paul Muldoon hosts a poet who reads two poems from The New Yorker, one of their own and one by another poet.

Off-Trail Learning – My friend Blake Boles interviews alternative-education thinkers and doers, often focused on unschooling. Check out his interviews with Dev Carey and Liam Nilsen. (He also interviewed me recently, if you are particularly interested in me.)

Planet Money – Short stories about and explorations of economics and the economy. You learn and are entertained. Check out “The No-Brainer Economic Platform,” about the six things that all economists agree on, and “The One-Page Plan to Fix Global Warming.”

Revisionist History – Malcolm Gladwell tells stories in that fascinating way he does, only on a podcast. Check out his episode on the song “Hallelujah.”

Seminars About Long-Term Thinking – The Long Now Foundation presents authors and thinkers talking about their ideas from the perspective that “now” is a long time—the last 10,000 years and the next 10,000 years. It’s fantastic—one of my favorites.

Sound Opinions – Pop/rock record reviews and conversation.

TED Radio Hour – Interviews with TED speakers on a theme.

This American Life – The prototypical podcast. Great stories.

This Week in Microbiology – Three microbiologists discuss recent microbiology research. It’s super nerdy and good. I loved keeping up with developments in this exploding field.

The Tim Ferriss Show – Author Tim Ferriss interviews very interesting people. Tim’s access is astounding and his knowledge base is wide enough that he can have interesting conversations with anyone. The theme is deconstructing top-level performance, but topics are all over the place. Chances are he’s interviewed someone you’re interested in, so look in his archives and start there.

Vox’s The Weeds – Very nerdy and very good political analysis. These folks are actually reading the original documents—laws, reports, policy papers, etc—and it shows. Outcome-relevant learning in political analysis.

Waking Up with Sam Harris – Some of the most interesting and inspiring conversations about science, philosophy, and spirituality that I’ve come across. Unfortunately, he also puts up a lot of episodes about Islamic terrorism, which are boring and quite skippable once you understand his perspective on the topic. His non-terrorism political rants tend to be quite interesting and often surprising, and it’s just lovely to hear him tear into Trump. I’d advise starting with an interview with one of his scientist or philanthropist guests, though, maybe “The Light of the Mind,” about consciousness with David Chalmers.

You Are Not So Smart – Each episode is about some facet of faulty thinking, why we fall for it and how to fight it. Clever and fun.